The State Of Scala

Twelve years ago, I turned to Scala in search of a “better” Java. Scala offers functional programming, interoperability with Java, support for concurrent programming, clean immutable data structures, expressiveness, avoidance of boilerplate code, and the list goes on. Scala has so many desirable qualities that once you master the admittedly steep learning curve, programming in Java feels awkward. Twelve years ago, Scala started to gain traction while the pace of innovation in the Java community slowed down after Java SE 6 was released. It was expected that Scala would grow. It was expected that Scala would make inroads to the holy grail of enterprise applications.

So, what happened?

Well, Scala did grow. Until about 2017, Scala was the most popular alternative JVM language. Let’s briefly take a look at the things that Scala did better than Java. There is plenty of verbosity and boilerplate in Java which Scala eliminates. This makes Scala programs more pleasant to write. Scala also frees programmers from having to do everything according to the OOP paradigm. It offers functional programming as an alternative. Scala has a better type system, better generics, it has operator overloading and last but not least, it offers better support for concurrent programming based on the actor model and -optionally- the Akka toolkit. Yet unfortunately, Scala never became a major player in the enterprise.

The reasons? It may be due to the fact that enterprise applications contain lots of legacy code and that switching to Scala would have meant abandoning existing legacy code and Java frameworks, which implies significant effort and cost. The Scala ecosystem is a bit fragmented and there may not have been many clear “industry standard” choices which managers love so much. Also, certain Java frameworks were built to overcome inherent flaws in the Java language and thus perhaps set off its disadvantages. In addition, it is difficult for enterprises to hire qualified Scala programmers, whereas it is relatively easy to hire Java programmers. Although every challenger to the mainstream has to face this problem, the complexity of Scala may have prevented a quicker adoption.

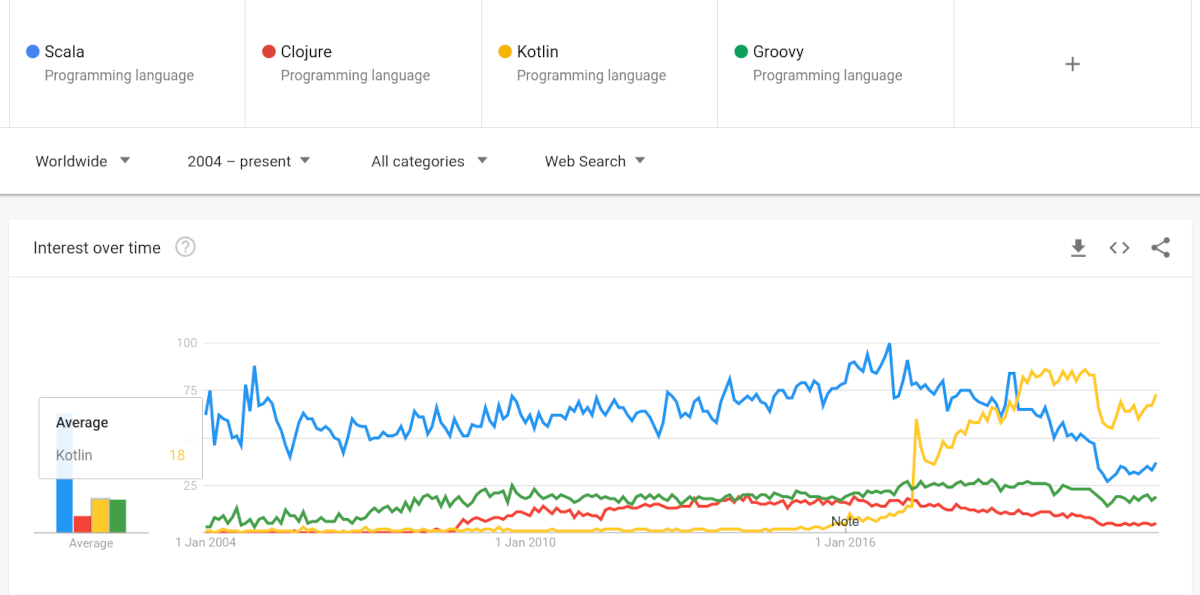

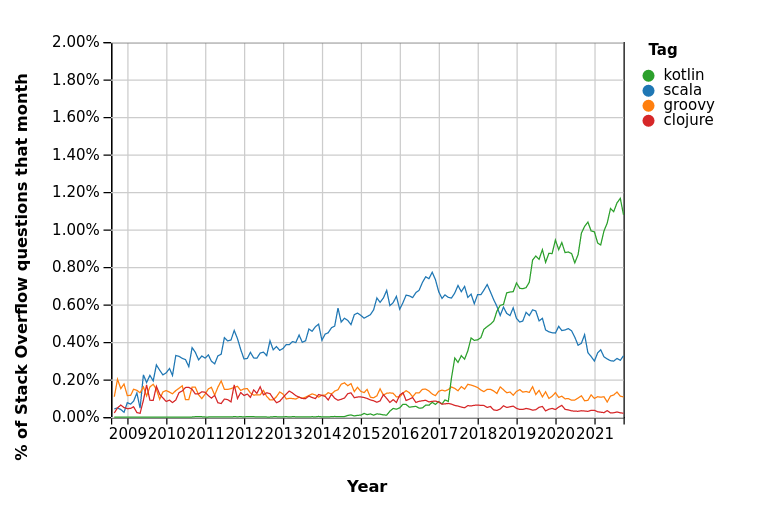

Let’s look at some trend developments over the said period of time. The following graphs are extracted from Google Trends and Stack Overflow Trends respectively. They represent the interest, based on search frequency, in four JVM programming languages, namely Clojure, Groovy, Kotlin and Scala. The line for Scala is blue in both graphs. While there are some deviations, these graphs make two things clear: (1) Scala has been dominant as an alternative JVM language for a long time. (2) Somewhere between 2018 and 2019, Kotlin overtook Scala and Scala began to decline.

Again, what happened?

Your guess is as good as mine, but I suspect it had something to do with Google throwing its weight behind Kotlin in 2017. Google even made it the preferred Android development language in 2019. At this point, one might ask: Why Kotlin? Why Android? It is not easy to answer this without venturing off-topic. In brief, Kotlin started out as a JVM language, just like Scala, aiming to be more versatile and more pleasant than Java. Like Scala, it combines OOP with functional programming, but it has a simpler type system and it feels much more lightweight than Scala. Coming from Java, Kotlin is easier to pick up than Scala. On the other hand, it lacks some of the more esoteric Scala features.

Something else happened as well. Java added lambda expression in version 8, opening up the possibility of functional programming. Kotlin became a multi-platform language relatively quickly, while Scala remained JVM-centered. Today, you can compile Kotlin natively or transpile it to JavaScript, giving the language a greater reach. By contrast, a native compiler for Scala appeared only in 2017, and while this is a laudable effort, it seems to have come too late. I think that Scala would have enjoyed greater acceptance if the original JVM compiler had been faster and if a native compiler was made available five years earlier. And, while you can use Scala to develop Android apps, few people are doing that today. Kotlin, on the other hand, is carried by the growth in that segment.

Perhaps the biggest elephant in the room, and the question one should really ask is why none of the alternative JVM languages, including Scala and Kotlin, has been widely adopted by the industry, or God forbid, overtaken Java. The modern JVM languages (I definitely include Scala) are technically superior to Java. However, according to the JVM Ecosystem Report 2020, Java still holds a whopping 87% market share in the JVM language segment. I am afraid, the answer is as simple as it is frustrating. Because technical excellence rarely decides market success. There are two major reasons for the continued Java dominance. First, when alternative JVM languages first appeared, Java had already reached critical mass. Second, Java is at home in the enterprise, especially in large enterprises, and these entities are somewhat resistant to change.

Ironically, one might say that Java is becoming the new Cobol. It is centered around business needs and it was good language for its time. It has enjoyed decades of success and it is absolutely everywhere today. Perhaps, the sun is setting on Java as a programming language, but it will stay around in the form of sheer market force for decades. – It’s going to be a really long sunset. New technologies may be promising, but business managers tend to prefer tried and tested ones, until something disruptive happens. Possibly, Scala was not disruptive enough to reshuffle JVM market shares in its favour. But one has to give credit to Scala for popularising functional programming in the Java world. After having spent decades in academic backwaters, functional programming finally made its way into mainstream business application programming.

In addition to functional programming, Scala has pioneered syntax that became popular such as infix notation, for comprehensions and pattern matching. It is a mathematically minded language that gives programmers an extreme range of expressiveness and problem solving approaches. One should not write it off yet. Scala 3 has just been released earlier this year. It is a major overhaul of the language and it features what is now possibly the world’s most advanced type system. According to the Scala home page, Scala 3 has undergone a cleanup and now offers a cleaner syntax. There is also a new (free) book. Scala 3 has dropped some old features and introduced a whole slew of new ones, mainly in the areas of types, contextual abstractions and metaprogramming. Only time will tell if Scala can stand its ground in the Java world and garner the recognition it deserves.